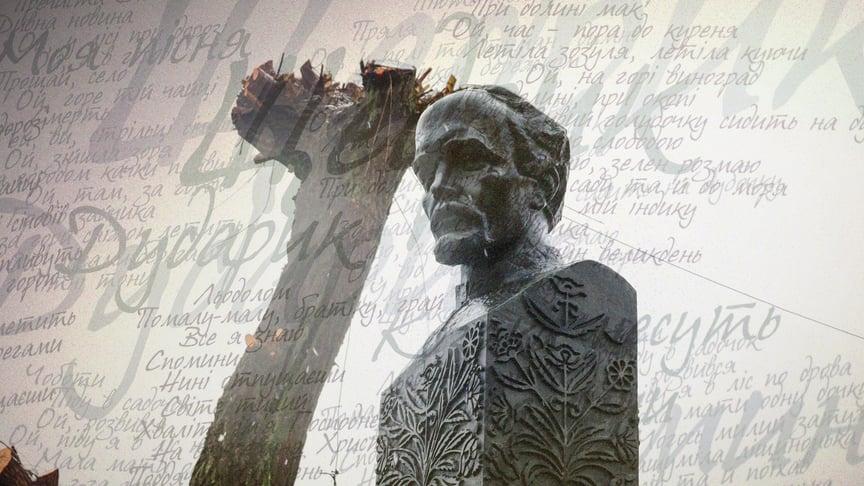

Five versions of "Shchedryk" and one bullet: a nod to Mykola Leontovych's legacy.

Galina was buried in Tulchin at the state's expense. The municipal cemetery holds the graves of her mother and sister, but they cannot be identified. The burial site of Leonovitch's father, priest Dmitry, remains unknown as well. In fact, many details surrounding the composer's life and death are either confusing or unresolved.

Hromadske traveled to Tulchin, where the composer lived from 1908, and to Markovka, the site of his death, to shed light on his story.

His wife was shy to play near him

According to Svetlana Lukashchenko, the director of the Leonovitch museum-apartment in Tulchin, nothing remains from the Leonovitch family in the village of Monastyrik, near Nemyriv, where the composer was born.

The house of his father in the village of Shershni in the Vinnytsia region, where Nikolai spent his childhood, as well as the composer's residence in Pokrovsk, burned down over 100 years ago. Fortunately, the house in Tulchin with the family's belongings has survived.

Before Nikolai's birth, the Leonovitch family had five generations of priests. At one point, Nikolai graduated from the Shargorod Spiritual School and the spiritual seminary in Kamianets-Podilskyi, but he did not continue the dynasty. His seminary diploma boasts straight A's — with only a top mark in church singing.

His father taught him music notation, singing, and playing musical instruments — in his youth, the elder Leonovitch even played the cello in a seminarian orchestra and led a choir (the museum-apartment even has a photo of this orchestra, showing that Nikolai closely resembled his young father).

After seminary, Nikolai became a teacher, instructing in rural schools and colleges in what is now the Vinnytsia region. At the same time, he earned the title of church choir leader in the regent class of the Court Chapel in St. Petersburg.

During this time, Leonovitch also found a partner. Klavdiya Zhovtkovich was the daughter of a priest from the Volyn village of Podlesie. They met in 1901 in the village of Tyvrov in the Vinnytsia region, where Nikolai taught at a spiritual school while Klavdiya was visiting relatives. They married the following year, and by 1903, they were parents to little Halinka. The next four years, the Leonovitches lived in Pokrovsk, where Nikolai taught at a railway school.

“In Pokrovsk, his younger children — Nadia and Vladimir — were born. And then: their infant son dies, Klavdiya falls gravely ill and undergoes a long treatment in Ekaterinoslav. Leonovitch leads a workers' choir, while his friend participates in anti-government demonstrations. This draws the police's scrutiny, prompting the composer and his family to move to Tulchin,” Svetlana Lukashchenko recounts.

Why Tulchin? Because there was an opening for a music and singing teacher at the local women's diocesan school. Not far from the town, his father served as a priest.

At the diocesan school, where the daughters of priests studied, Leonovitch immediately organized a choir. At his request, the girls brought texts and melodies of folk songs from their villages, along with various ethnographic materials. They signed their photographs for their beloved teacher and embroidered purses for him — all of which are now part of the museum's exhibition.

Leonovitch compiled the sheet music of the collected songs in a special suitcase, which is also among the exhibits. According to his daughter Halina, when their father opened the suitcase and played the recordings on the piano, no one was allowed to interrupt him. Only his wife would quietly bring him tea...

“Leonovitch's parents had good hearing and voices, and sang beautifully, as did his sisters. So he could not tolerate when any of his students sang off-key or played instruments poorly. He didn’t shout; he just looked at the student who hit the wrong note and turned red. His wife never even sat at the piano next to him to avoid irritating him,” Svetlana shares.

The Leonovitches changed apartments seven times in Tulchin. They moved into the one that is now the museum in 1918. It was part of the diocesan office building that had been vacated when the Bolsheviks closed the women's diocesan school.

In this five-room apartment, Leonovitch composed the third, fourth, and fifth versions of "Shchedryk." Svetlana Lukashchenko believes that "Shchedryk" first sounded in Tulchin — performed by the choir of Leonovitch's students on Christmas in 1915 at the church of the diocesan school. In the autumn of 1920, the composer hosted the choral chapel of his friend Kyrill Stetsenko in Tulchin, which performed several of Leonovitch's works during a concert at the Pototsky Palace.

“After the concert, Stetsenko once again invited Nikolai Dmitrievich to finally move to Kyiv. But he said he would move when he finished the opera 'On the Mermaid's Easter.' However, he did not have time to finish it,” says the director of the Tulchin museum.

In January 1921, Leonovitch donned a coat made by Klavdiya from scraps of cloth, a matching hat and pants crafted by his wife, grabbed some pastries for the road — and left his Tulchin home. He intended to be gone for a few days — but it turned out to be forever.

Rumors of an affair?

In one of the photographs of the students of the Tulchin diocesan school, preserved in Markovka, there is a dark-haired young girl with a magnificent braid. Nadiya Tanashovich was the daughter of a priest from the village of Strazhgorod, located 8 kilometers from Markovka. She wrote poetry, was knowledgeable about Ukrainian folklore, and it was to her that Leonovitch proposed to create the libretto for the 2nd and 3rd acts of the opera "On the Mermaid's Easter." The opera was based on a fairy tale by Boris Hrinchenko, but Nikolai Dmitrievich found the story sufficient only for the first act.

Why did Leonovitch turn to a village girl with poetic talent at the county level? Why not, for example, to Pavlo Tychyna, who served as a master of ceremonies during the Stetsenko choir's tours and was a good acquaintance of the composer? Or to other poets?

“Periodically, publications arise in which Nadiya is referred to as almost Leonovitch's mistress. I consider all this gossip. She sang well, knew many songs, but a mistress? He had a wonderful relationship with his wife, what mistress? He approached Nadiya because, remember, what times they were. Where was he to find those Kyiv poets?” insists Oльга Прокопенко, director of the Leonovitch museum in Markovka.

It was to Nadiya in Strazhgorod that Leonovitch traveled from Tulchin in January 1921. He walked, staying overnight with acquaintances in farms and villages. And on the roads, where due to the rampant banditry at the time even dogs were afraid to venture out, nothing unpleasant happened to him. He reached Nadiya, worked with her all day on the opera, and then headed to Markovka, where his father served as a priest and where his daughter Halina had been living since the summer of 1920.

“It was said that there was a wreath from Nadiya Tanashovich at Leonovitch's funeral. What wreath? She came from a poor family with many children and even had to work with her sisters. How could she afford to buy that wreath?” says Svetlana Lukashchenko.

She adds that Halina never commented on her father's relationship with the priest's daughter Tanashovich.

Nadiya later married a former Kotovets, with the surname Ivanov. She gave birth to two sons and worked in children's shelters in the Vinnytsia region. She never completed the libretto for the opera. There is no information on the publication of any of her poems.

Chekists, policemen, and a murderer

On the evening of January 22, 1921, while Nikolai was visiting his father, a man asked to stay the night with them. They let him in: where else would a traveler find shelter if not in a priest's house? In the early morning, this man shot the composer in the stomach.

This is the skeleton of a story that has accumulated