12 years in prison for donations to a shelter fund. The story of a guy from Donbas incarcerated in Russia.

“I suspected who these people were and what they were capable of”

The Efimovs hail from Snezhnoe, a mining town located 80 km east of Donetsk, which has been under occupation since 2014. After the onset of hostilities, the family briefly left Donbas but returned, as it was mostly quiet in Snezhnoe, recalls Kirill.

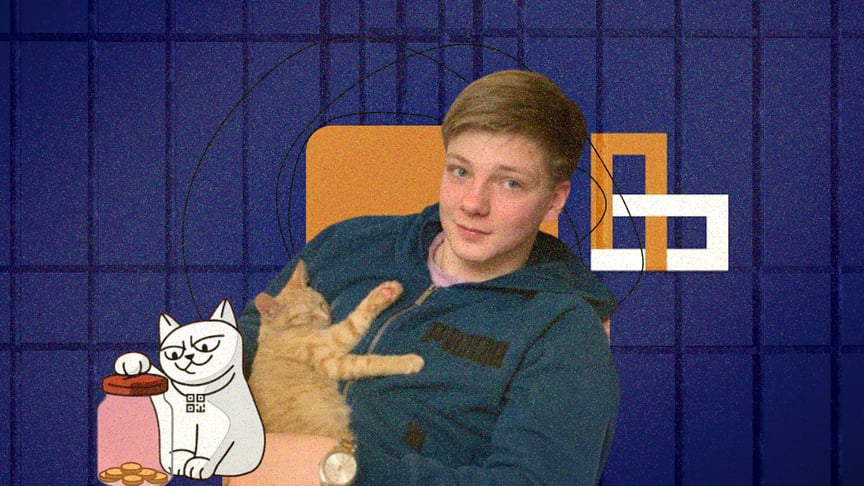

In his childhood, Daniil practiced Greco-Roman wrestling. Due to an injury and the war, his interests changed: he began to draw, write poetry, and carve wood. Despite the occupation and his parents' stance, who insisted on obtaining Russian citizenship, the young man maintained his pro-Ukrainian views.

“After the full-scale invasion, Daniil switched to speaking Ukrainian with his close ones and friends. Of course, he didn't make public statements, as it could have been dangerous,” shares Kirill.

Daniil completed school remotely in a territory controlled by the Ukrainian government. He considered higher education institutions in Ukraine and Poland but didn't manage to submit his applications. Thus, at his father's request, he went to study at the Southern Federal University in Rostov. He planned to enroll at Taras Shevchenko National University in 2024.

After the war began, Kirill left home and went to Turkey, while Daniil stayed with relatives in Snezhnoe. In December 2023, Daniil and his girlfriend, along with his father, intended to fly to Istanbul to visit his brother. He planned to restore his Ukrainian passport and thought about relocating from the occupation. However, everything went awry.

Daniil didn't want to use a Russian passport, so he resolutely traveled with his Ukrainian one. This became the reason for his detention at the airport in Volgograd. His father and girlfriend were not informed of anything.

“I had just shown my documents when they took me in for interrogation. They asked for the number of my relatives. I opened my phone to find it, and immediately I heard: ‘What are you turning away for?’ — and they snatched the phone from my hands. I was terrified because I suspected who these people were and what they were capable of,” writes Efimov from prison.

The Russian security forces discovered bank transfers on his smartphone. Questions flooded in: what was this for and who was it for? At that moment, 18-year-old Daniil tried until the last moment not to answer them, but due to threats, he eventually confessed.

Meanwhile, Daniil's father and girlfriend stayed in Volgograd searching for a lawyer. Kirill believes that the lawyer they found was a setup, as he forced the girl to go for interrogation, where the Russians tried to extract testimony about a crime from her, although it was not mandatory.

“I lied until the very end. I said it was for humanitarian aid for civilians. In the evening, they released me to a hotel. The next day, under the pretext of signing documents, I was handed over to two police officers. Without explanation, they threw me into a dark room resembling a basement,” recalls Daniil.

The Russian police drafted a protocol against Daniil allegedly for using offensive language in the area. The court placed the young man in custody for 13 days. The authorities did not immediately admit that they were holding the student while his relatives tried to find him.

Then, the arrest was extended for another 10 days, supposedly for hooliganism. Daniil labeled these accusations as fabricated.

“Such baseless and consecutive arrests are called ‘carousel arrests’ — they are used by the authorities to buy time and prepare materials for initiating a criminal case. They haven't come up with any other ‘legal’ way to detain a person yet,” explains a representative from the Russian human rights organization, First Department.

“When someone above was taking a bath, we got flooded”

In the Volgograd detention center, they provided torn underwear, and he was thrown onto the floor in a cell — there wasn't enough space, he recounts in letters. Later, he was moved to a special block, in complete isolation, where no one could see the “traitors” and “Ukrainians,” who were not supposed to be there.

“Soon we were transferred to ‘our place’ — the basement. The window there was bricked up, there was almost no light, and the walls were covered in mold; some walls had collapsed. When someone above was taking a bath, it literally rained on us, we got flooded,” describes the conditions of Daniil’s confinement.

One cellmate loved to sing Ukrainian songs. For this, he was severely beaten; others were lightly kicked in the sides. Then they were taken to an office, where one of the prisoners had a bag placed over his head and was forced to shout “Glory to Russia” in front of a portrait of Vladimir Putin. They beat him, suffocated him with the bag, and made him learn the Russian anthem. After that, the prisoners had to sing it every day — loudly enough for everyone to hear.

Even before the “investigation” began, Daniil was once forced to sign a confession. He refused, demanding to speak with a lawyer first. Then a man entered the office, introducing himself as a “Wagner” member.

“The ‘dialogue’ began with blows, curses, and threats to take me to the forest, where I would sign everything they said. We were already heading to the exit to go to the forest, but instead, I was abruptly thrown into a cage, and they left,” writes the young man.

He didn't understand what was happening. Everything was decided by the lawyer and his father, who chose a defense line based on “sincere repentance” to reduce the sentence. The young man was transported to Rostov.

“A Misconception About the Armed Forces of Ukraine”

During a hearing in the Rostov Regional Court, Daniil's neighbor from the dormitory, Vyacheslav Nikiforov, testified. He claimed that there was “constant negativity” from Efimov: he called Russia an aggressor, accused it of committing crimes against civilians, and criticized Putin.

Daniil's group supervisor from the university, Lyudmila Zaitseva, stated that the young man “categorically refused to participate in patriotic events and educational programs.” In particular, they concerned the importance of knowing Russian history.

In the “sentence,” allegedly based on Daniil's words, it is noted that after the war began, he was constantly stressed since he read Ukrainian news about Russian crimes and heard this from relatives located in territory controlled by the Ukrainian government.

“Under the influence of these publications and information received, he (Daniil — ed.) formed a false impression of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, their actions, and the necessity of financially supporting the Ukrainian army,” states the case materials.

In July 2024, Daniil was sent to a high-security colony for “treason.”

How Russians Illegally Arrest Civilians

Elizaveta Sokurenko, head of the military crimes documentation department at the ZMINA Human Rights Center, commented to Hromadske that Ukrainian human rights defenders are aware of other similar cases where Russians “frame” Ukrainians for “treason.” For instance, in June 2023, Russian soldiers detained two young men in Donetsk, accusing them of collaborating and assisting the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

This is one of the most common charges under which Russians initiate criminal proceedings against Ukrainian civilians, particularly those who, due to life under occupation, were forced to obtain a Russian passport,” says Sokurenko.

Since the beginning of the large-scale war, the number of cases related to terrorism, espionage, and treason that Russians fabricate against Ukrainians has rapidly increased. If in 2022, various sources reported 500 cases, by the end of 2024, there were about 5,000 (over almost three years).

The human rights advocate notes that courts are biased in favor of the prosecution, and defendants “confess” under torture or threats of further torture. The systematic abuse of the judicial process by Russians can be considered not only a war crime but also a crime against humanity.

“There is no procedure for returning arbitrarily detained civilians to territories controlled by the Ukrainian government. Most of these individuals are held in detention without any charges, and neither the International Committee of the Red Cross nor international missions have access to them,” explains Sokurenko.

She noted that although illegally detained civilians have been returned to Ukraine during prisoner exchanges, their number is small — 168 people since 2022. In October 2024, Oleg Slobodyanik, a representative of the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War, stated that there could be more than 14,000 civilians held captive by Russians, but only 1,300 have been confirmed.

Evgeny Smirnov, a lawyer from the Russian human rights organization